Clapham novelist on her newest release

Clapham novelist on her newest release

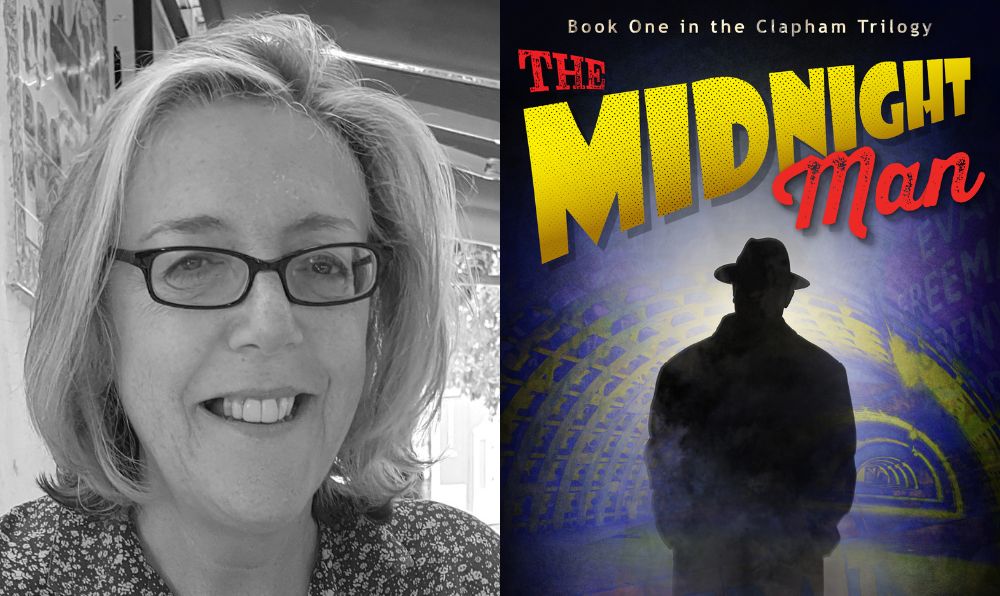

Clapham-based author Julie Anderson tells us about her latest thrilling release and the local inspirations behind it…

Julie Anderson’s latest crime novel, The Midnight Man, releasing on 30 April 2024, is set in Clapham in 1946. A Clapham local, Julie has steeped the story in local history. We caught up with her so she could tell us more about the novel, its setting, and the history behind it, including a fascinating hospital run by and for women…

The Midnight Man is set in Clapham in 1946. Why is it set in that time and place?

For a combination of reasons. I wanted my next book to have contemporary relevance, especially after the pandemic, but I didn’t want to write about COVID. So I decided to write about a similar time when, after a great and tragic upheaval, people were adjusting to a new reality. The obvious parallel was the period after World War II. An outpouring of relief and joy that it was over was followed by austerity and hard times. Some people wanted to return to how things were before, others had ideas about how things should change. The difference being that from 1945 onwards a new society was being forged. I suppose I also wanted to remind people of what was possible.

The NHS was part of that (the NHS Act passed in November 1946) so I thought that a hospital might be a good location for my book, enabling me to show changes taking place. Then I found out about the South London Hospital for Women & Children. Clapham has been my home for over thirty years and I used to walk past the empty hospital buildings on my way to and from the tube every day, but I knew little about it. When I began researching, I discovered that it was the largest woman-only hospital in the UK, run exclusively by and for women. This made it both unusual and very apposite for my book.

During the war, women had been running things at home while most of the men were away fighting. They’d enjoyed responsibilities and freedoms otherwise denied them. Once the war ended, however, they were expected to return to their ‘traditional’ roles. Given that not all women, especially younger ones, wanted to return to these pre-war certainties, the existence of an institution which encouraged women to be professional medics, not housewives, created tension. The South London, or the SLH, had to constantly prove its worth and credentials, often against opposition from the predominantly male establishment. As did the women who worked there. Tension is intrinsically of interest to a writer.

THE BEST OF LOCAL CULTURE:

Tell us about the research process for the book?

I was fortunate to find a retired consultant surgeon who worked there in the 1980s – she was standing as a Green candidate for Wimbledon council. She supplied me with photographs and literature belonging to the early hospital. I also spoke with a former midwife and former nurses, all of whom fondly remembered the hospital. There is a Facebook group, to which I now belong, called South London Women’s Hospital occupation 1984─85 where those who protested at the hospital’s closure, many of them staff and patients, reminisce and organise the occasional get together.

I spent a lot of time at the Lambeth Archives, reconstructing the hospital in my mind, using the architect’s plans. I also read minutes of meetings of the South London’s management board and similar minutes belonging to other hospitals of the time and this helped to give me an understanding of the context. It is instructive that, despite there being an acute shortage of nurses after the war, the SLH never had a problem attracting nurses; it was a place where women wanted to work.

There was also a lot of reading to do about that period, which I found fascinating.

What did you uncover that surprised you?

The lack of any history or biography of the hospital and its founders was a real shock.

The astonishing determination and resilience of the founders of the hospital was hugely impressive. The two women surgeons who raised the funds for the hospital, aided by their friends, were the first of a whole host of remarkable women. Maud Chadburn became a surgeon despite her minister father’s denunciation from the pulpit (he said he would rather his daughter died than became a doctor) and she was joined by Eleanor Davies-Colley, the first woman to be admitted to the Royal College of Surgeons. Today there is a road in Clapham named after Maud and the Chadburn Academic Clinical Lectureship at St George’s Hospital, Tooting. Eleanor had a lecture theatre at the Royal College of Surgeons named after her, though, following a reorganisation that has closed. There is, as far as I’m aware, no history of the hospital.

MORE ON CLAPHAM:

Where are your favourite locations that you feature in the book?

I am very fond of all of them, but the most atmospheric would be the deep shelters. As you emerge from Clapham South underground station onto Clapham Common Southside, about a hundred yards away you’ll see a concrete pillbox of a building, on the common very close to the busy road. Currently graffiti covered, this unlovely and unloved building is the entrance to a fascinating world beneath the ground.

The deep shelters were built too late for the Blitz, but this warren of tunnels came into its own in 1944 when German rockets bombarded London. South Londoners descended, nightly, in the lifts, to their bunk space in the shelter, which held canteens, lavatories, washrooms and a medical centre. Apparently, it was quite sociable, people played music, sang songs and played cards and other games as the rockets fell overhead. All this while the underground trains rumbled above them, the shelters being deeper even than the underground lines.

The shelters are still there, and London Transport Museum runs regular tours of them (although you’ll have to be reasonably fit to manage the 180 steps up and down). The tunnels have lost none of their atmosphere. They feature, not only in The Midnight Man, but in the other two books which will make up the trilogy of which The Midnight Man is the first.

Which locations are similar today?

Aside from the tunnels, a building which is similar, then and now, is Westbury Court, the 1930s apartment building above Clapham South underground station. Places like the Odeon cinema, Balham Hill, where my characters go to watch the latest films, exist but have been repurposed. The cinema is now a wine warehouse. The hospital buildings are a supermarket and apartments. The common is, of course, still there as is Sugden Road, where one of my main characters lives in a rented Victorian terraced house. Her working-class family wouldn’t be able to afford that now.

Tell us about the characters and storyline?

It’s a murder mystery. The story begins on a cold dark night, as a devastated London shivers through the transition to post-war life. A young nurse goes missing from the South London Hospital and her body is discovered hours later behind a locked door. Two women from the hospital join forces to investigate. Both are determined not to return to the futures laid out for them before the war and these unlikely sleuths must face their own demons and dilemmas as they pursue the killer.

What would you like readers to take away from the book?

Of course, I hope they’ll have enjoyed the book and want to follow the fortunes of my characters in the remaining books. Aside from that I hope people will take away the idea that, even in what seems the worst of times, good, big change for the future can be achieved. It should also remind people what it was like when medical treatment was not free. As Joni Michell sang, you don’t know what you’ve got ‘till it’s gone.

The Midnight Man by Julie Anderson is published on 30 April 2024 by Hobeck Books, the first in the Clapham Trilogy.

For London Transport Museum tours check the website at London Transport Museum and look for Hidden London or sign up to their Newsletter for regular alerts about tours and get priority booking access.

For more, free, information about the Deep Level Shelter visit The Clapham Society’s website at Articles – The Clapham Society