William and Jane Morris

William and Jane Morris – in a new light

We talk to art historian Dr Suzanne Fagence Cooper about the legacy of William and Jane Morris, their association with Merton Abbey Mills and how their unconventional lives may have lessons for us all…

‘The true secret of happiness lies in taking a genuine interest in all the details of daily life…’

You might be forgiven for thinking that this quote is taken from a modern-day book on mindfulness but it’s actually William Morris’s words of wisdom and a mantra the Victorian artist and social activist lived by. A pioneer of the Arts & Crafts movement, he extolled the virtues of living well, more simply and surrounded by beauty; and his prints, still much used today in fashion and interiors, reflected the detail in nature – biophilic design before its time, perhaps.

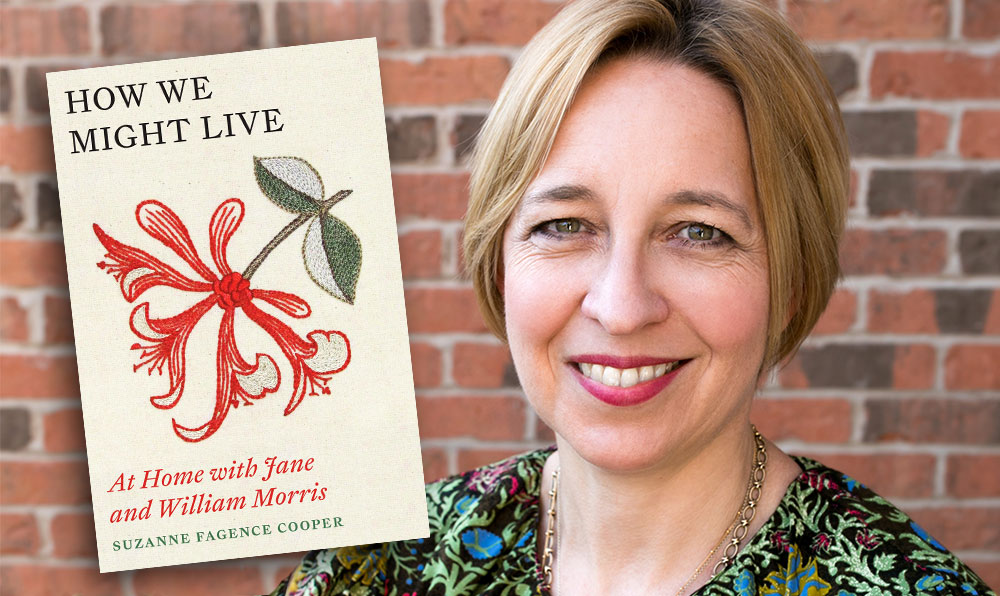

In her new book, How We Might Live, which she will discuss at Wimbledon BookFest in June, Dr Suzanne Fagence Cooper sheds light on their approach to life, their relationship – and why Jane deserves more credit than a mere footnote in history as simply his wife and artists’ muse.

Jane, as a talented and self-taught embroiderer, played a big part in the Morris business and together with William, created several incredible houses that reflected their aesthetic. They also opened up their homes to artists and thinkers, becoming hubs for creativity and expression.

It was an unconventional relationship. They met in Oxford when William visited the city with his friends, the Pre-Raphaelite artists Dante Gabriel Rossetti and Edward Burne-Jones, to work on the Oxford Union murals. Jane was from an extremely poor and humble background. The artists noticed her at the theatre – she was a striking, tall girl with strong features and tightly curled hair – and they followed her through the streets until she agreed to model for them. Says Dr Cooper: “She would have been quite self-conscious of her looks but there was a nobility about her. And the artists wanted what they called “stunners” for their work and not conventional beauties.”

Understandably wondering if their intentions were dubious, she didn’t show up for her first sitting. When she did return, she watched from the sidelines for the first summer. William would read to her and she was soon absorbed into this world of art and poetry – and she learned fast.

William fell in love and they married. “You can see how she quickly changes. A very early photo shows her closed pose where she is stooping; in another photo soon after you can see that she is showing her hands, neck and hair and demonstrating a professional pose as a model.”

Indeed, she changes everything about herself. “She changes her accent, she learns how to look after a household, learns a number of languages and how to play music. And she always wants to learn more and more, moving on from one language and instrument to the next.”

There was also the matter of Jane’s lovers but their marriage weathered her affairs with both Rossetti and adventurer Wilfred Scawen Blunt.

Says Dr Cooper: “William didn’t care about convention. He lived how he wanted, he married the woman he wanted and they created homes that they opened up as hubs for other artists, poets and friends – it is this spirit of generosity that really comes across.”

Together they had two daughters and their households were busy ones, with Jane becoming an incredible hostess (Dr Cooper’s book features previously unpublished recipes from Jane’s own repertoire). Their homes included Kelmscott Manor in the Cotswolds, Red House in Kent (both are open to the public) and Kelmscott House in Hammersmith (The William Morris Society is located in the basement and coach house).

They also had a two-room room cottage in Merton Abbey Mills (which is no more but stood where Sainsbury’s now is) so William could have a place near to his new factory, if he did not want to commute home.

Until the 1880s, William’s textile weaving was done out of his home in Hammersmith. As he moved into bigger textile production, in particular, carpets, he and his friend William De Morgan looked for a bigger space. But the requirements were very specific – a steady and reliable water source being one of them. “They thought that their ‘fictionary’ as they called it – rather than ‘factory’ – didn’t exist until they came across Merton Abbey Mills, which was perfect. It was surrounded by nature and there are stories of William gathering up huge bunches of blooms and catching the train back home with them.”

William and Jane’s eldest daughter Jenny was diagnosed with epilepsy as a teen. At the time, there was little treatment available and it carried a stigma. Again, the couple defied the conventions of the Victorian era by choosing to care for her themselves, rather than sending her away to an institution.

Jane was not only dealing with her daughter’s ill health, but also her own, suffering from a chronic condition that caused her a great deal of pain, possibly in her back or having a gynaecological cause. “She refused opiates for the pain as she’d seen Rossetti become addicted and his wife Elizabeth Siddal died from an overdose of laudanum. She managed her pain in other ways by keeping busy.”

One story reveals how Henry James came to visit, having seen Jane in Rossetti’s paintings and heard about her in his poetry, to see if she lives up to her portrayal. The author describes Jane in quite disparaging ways: ‘a thin pale face, a pair of strange sad, deep, dark Swinburnian eyes, with great thick black oblique brows, joined in the middle…’ He goes on to say that she lay on the sofa with toothache, a handkerchief at her face…. ‘a dark silent medieval woman with her medieval toothache…’

Says Dr Cooper: “What strikes me about Jane is her resilience. She is in pain, has a very sick daughter and William gets rheumatic fever.

“There’s a side to her you don’t see in the paintings. Her friends describe her as having a ‘delicious chuckling laugh’. She would also create these beautiful books of quotations, which she would decorate in her own distinctive style.”

Together, William and Jane dispelled the idea of what a Victorian home should be. “We think of the Victorians as having private spheres with women staying at home while the men worked. They were very different. They opened up their homes. Their houses were also quite modest. William described his ideal residence as having a sanded floor, whitewashed walls and with green trees and running water outside. He believed that you don’t need a great deal of belongings as long as what you do have is well made.”

Their homes were always near water – he not only needed the running water to produce the textiles but also to inspire him. Several of his designs are named after rivers such as the Wandle and the Wey.

Suzanne is very much looking forward to sharing insights from her new book at Wimbledon BookFest. “I can’t wait to see the reaction and to hear the questions, and also to see what other writers and artists are doing – much as William and Jane would have done – they’d have loved BookFest!” νT&L

How We Might Live: At Home with Jane and William Morris is out on 9 June / Hardback / £30, Quercus Books

Find out more on 12 June

Visit wimbledonbookfest.org for tickets and more info